On January 14th, the veteran Ukrainian politician Yulia Tymoshenko was charged with offering bribes to members of parliament. She reportedly offered bribes to members of Volodymyr Zelensky's party. Her story intersects with the larger forces at work in the Ukrainian parliament, writes Konstantin Skorkin in an article originally published by Carnegie Politika.

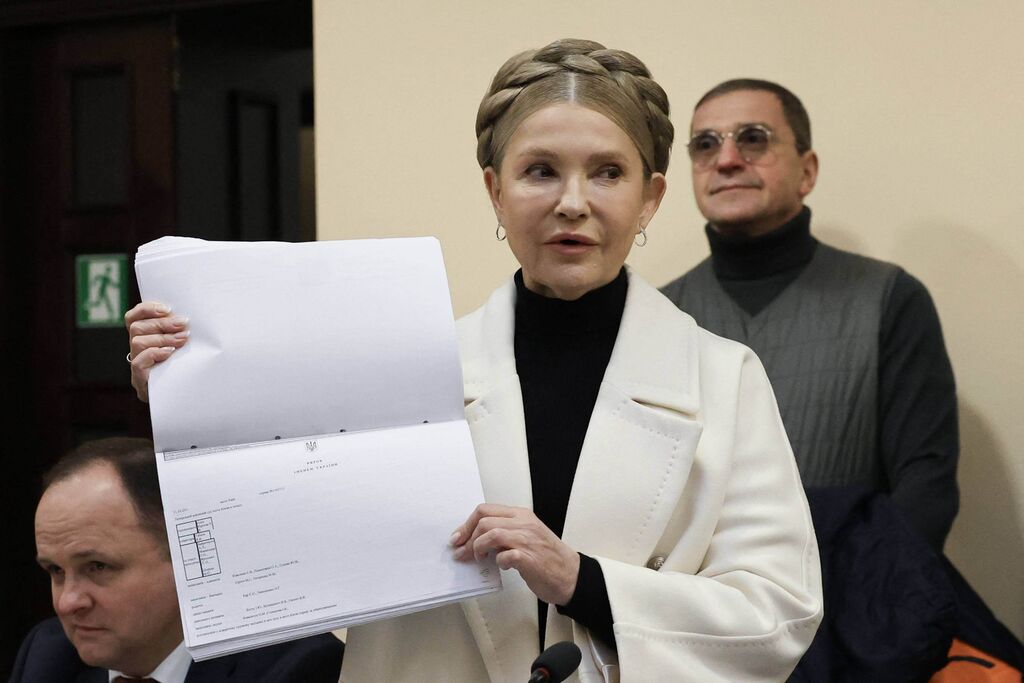

Yulia Tymoshenko speaks as she attends her pre-trial hearing at a court in Kyiv on January 16, 2026. Photo: ANP / Stringer / AFP

Yulia Tymoshenko speaks as she attends her pre-trial hearing at a court in Kyiv on January 16, 2026. Photo: ANP / Stringer / AFP

The veteran Ukrainian politician Yulia Tymoshenko appeared to have retired from the fray once and for all, spending her final years on the fringes of key events. But unexpected accusations against her of bribing parliamentary deputies have propelled her to the heart of the country’s political life once again.

The Tymoshenko scandal reflects the fact that the center of Ukrainian politics is once again shifting to parliament. The fight for parliamentary deputies’ votes is heating up again, and Ukraine’s domestic political crisis is entering a new phase, opening a window of opportunity for even half-forgotten politicians.

Tymoshenko's political career

To detail Tymoshenko’s career would be to recap the political history of Ukraine’s first twenty-five years of independence. Very briefly, she was a prominent figure in the new world of Ukrainian business in the 1990s, dubbed the 'gas princess'. She entered politics through her connections to then prime minister and now convicted criminal Pavlo Lazarenko, becoming an equally prominent representative of the opposition to then president Leonid Kuchma. She was first imprisoned in 2001, serving forty days in a pretrial detention center.

In the mid-2000s, Tymoshenko became one of the icons of the Orange Revolution, after which she reached the pinnacle of her career, twice serving as prime minister and running for president. After her opponent Viktor Yanukovych emerged victorious in the 2010 presidential election, Tymoshenko again became an opposition leader and also a victim of political persecution, spending more than two years in prison. Following the second Maidan revolution in 2014, she was triumphantly freed, but lost the presidential election again — this time to Petro Poroshenko.

To detail Tymoshenko’s career would be to recap the political history of Ukraine’s first twenty-five years of independence

After this, Tymoshenko’s political career waned, as she had become too closely associated with the past. The final nail in the coffin came with the 2019 presidential election: until that point, she had still been considered a viable alternative to Poroshenko, but then actor-turned-presidential hopeful Volodymyr Zelensky upended all the old elites’ plans.

Tymoshenko came third in that election (behind Zelensky and Poroshenko), and parliamentary elections held that same year resulted in a modest faction for her Batkivshchyna (Fatherland) party. Marginalized, she assumed the mantle of a socially conservative populist appealing to rural voters in agricultural regions.

Wartime politics

With Russia’s full-scale invasion, Tymoshenko faded into the background, unable to find a place in the new patriotic consensus. She became critical of the government, condemning the new mobilization law [in 2024] and the restrictions on consular services for Ukrainians abroad. At the same time, she cultivated her image as a Ukrainian Trumpist: she fought against the legalization of cannabis, a 'gender agenda', and other apparent challenges to patriarchal Ukraine.

Tymoshenko occasionally found herself embroiled in minor political scandals, such as over her luxury vacation in Dubai at the height of the fighting. In the summer of 2025, she took part in a campaign to limit the powers of the independent anti-corruption agencies NABU and SAP, calling them instruments of 'external control' and plans to curtail their authority an act of 'decolonization'. That was all perfectly in keeping with her new image as a socially conservative anti-globalist.